Johannesburg’s Apartheid Museum, assembled by a multi-disciplinary team of architects, curators, film-makers, historians and designers, takes the visitor on a powerful emotional journey into South Africa’s past, bringing to life the story of a state-sanctioned system based solely on racial discrimination.

After a few hours at the Apartheid Museum you will feel that you were in South Africa’s townships in the 1970s and ’80s, dodging police bullets or teargas canisters, marching and “toyi-toyiing” with thousands of school children, or carrying the body of a “comrade” into a nearby house.

The museum has become one of Johannesburg’s leading tourist attractions, an obligatory stop for visitors and residents alike.

The museum, with its large blown-up photographs, metal cages and monitors replaying scenes from South Africa prior to 1994, is situated next to the Gold Reef City casino and theme park, five kilometres south of Joburg’s city centre

It is appropriate that the first museum on apartheid in South Africa should have opened in Johannesburg, where at the turn of the 20th century there was a sudden convergence of people of all races, from around the world, for various different reasons – mostly to do with war and gold.

The museum came about as part of a casino bid in 1996. Bidders were obliged to include a social responsibility project; the winning consortium said they would build a museum, and spent in the region of R80-million making good on their commitment.

The museum occupies approximately 6 000 square metres on a seven-hectare site comprising recreated veld and indigenous bush habitat containing a lake and paths alongside a stark but stunning building.

“The synergy between the natural element and the building finish of plaster, concrete, red brick, rusted and galvanised steel, creates a harmonious relationship between the structure and the environment,” says John Kani, a famous South African actor and the chairman of the museum’s independent board of trustees.

A multi-discipliniary team of curators, filmmakers, historians, museologists and designers was assembled to develop the museum’s exhibits, which set out to animate the apartheid story using blown-up photographs, artefacts, newspaper clippings, film footage and more.

Tickets for the museum are plastic credit-card size cards indicating either “Non-white” or “White”, and with one in your hand, you know you have begun a harrowing journey.

As you swing through the turnstile on your historical journey from the early peoples of South Africa to the birth of democracy in the country in 1994, cages greet you, and inside the cages are blown-up copies of early identity cards, identity books and the hated passbooks and racially tagged identity cards.

The rest of the museum is just as graphic:

- A large yellow-and-blue police armoured vehicle, nicknamed a “casspir”, in which you can sit and watch footage taken from inside the vehicle driving through the townships.

- Dangling from the roof, 121 nooses representing the political prisoners hanged during apartheid.

- A 16 June 1976 room with a curved wall of monitors showing footage of that day from around the world.

- A cage full of weapons that were used by the security forces to enforce apartheid.

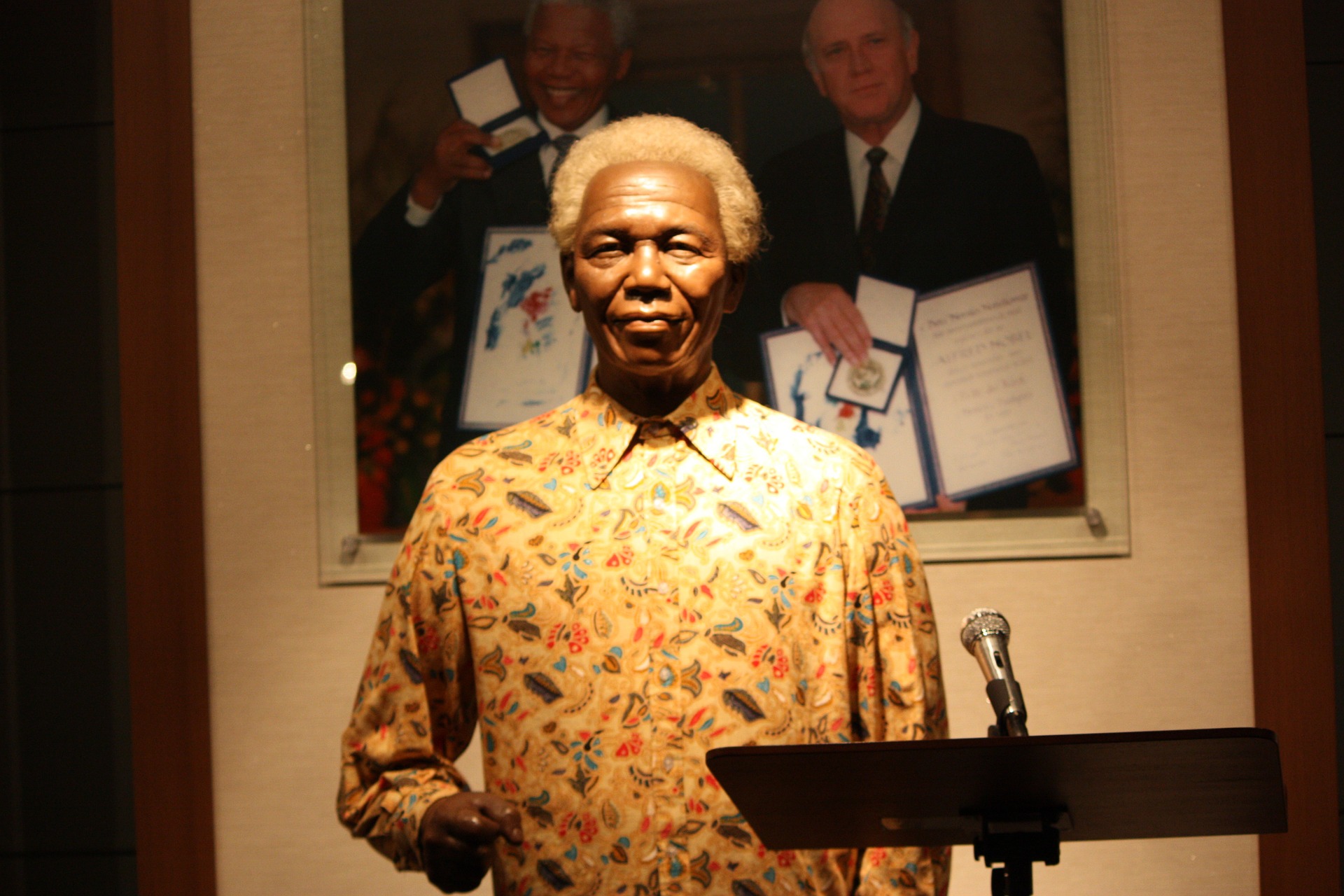

- Footage of a remarkable 1961 BBC interview with Nelson Mandela when he was in hiding from the authorities, as well as footage of prime minister Hendrik Verwoerd addressing a crowd in English, explaining how the country could be happily ruled only when its races were separated.

At times you feel overwhelmed by the screens and the sound and the powerful images they are projecting. The museum leads you through room after room in a zigzag of shapes, some with tall roofs, some dark and gloomy, some looking through to other images behind bars or cages that evoke the evil of apartheid.

And just when you feel you can’t tolerate the bombardment of your senses any longer, you reach a quiet space, with a glass case which contains a book of the post-apartheid Constitution, and pebbles on the floor.

You can express your solidarity with the victims of apartheid by placing your own pebble on a pile. You then walk out into a grassland with paths which take you to a small lake – you may need this reflective time.

There is also a recording studio in which visitors can leave their experiences under apartheid, if they had any, for others to hear.

“It is not only important to tell the apartheid story, but it is also important to show the world how we have overcome apartheid. There certainly is a lesson for other countries, and this will be related through the complexity and sheer power of the installations,” explains the museum’s director, Christopher Till.

For Kani, the overriding message “is to show local and international visitors the perilous results of racial prejudice and how this, in the case of South Africa, nearly destroyed the country, and in so doing destroyed people’s lives and caused enormous suffering.”

An architectural consortium consisting of five leading architectural teams was assembled to design the museum. The result, says Kani, is “a triumph of design, space and landscape fused into … a building of international significance.”

Till agrees. “The building itself has power, which is what is needed to put across the powerful message the museum has to offer.”

Source: City of Johannesburg